| |

| 首页 淘股吧 股票涨跌实时统计 涨停板选股 股票入门 股票书籍 股票问答 分时图选股 跌停板选股 K线图选股 成交量选股 [平安银行] |

| 股市论谈 均线选股 趋势线选股 筹码理论 波浪理论 缠论 MACD指标 KDJ指标 BOLL指标 RSI指标 炒股基础知识 炒股故事 |

| 商业财经 科技知识 汽车百科 工程技术 自然科学 家居生活 设计艺术 财经视频 游戏-- |

| 天天财汇 -> 商业财经 -> 当年中学教科书中描写万恶的资本主义时,为什么资本家宁愿将牛奶倒掉也不分给穷人? -> 正文阅读 |

|

|

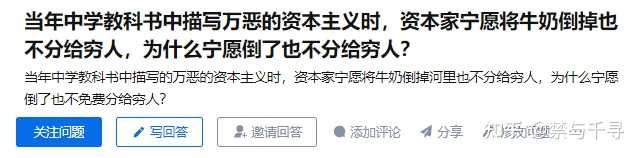

[商业财经]当年中学教科书中描写万恶的资本主义时,为什么资本家宁愿将牛奶倒掉也不分给穷人? |

| [收藏本文] 【下载本文】 |

|

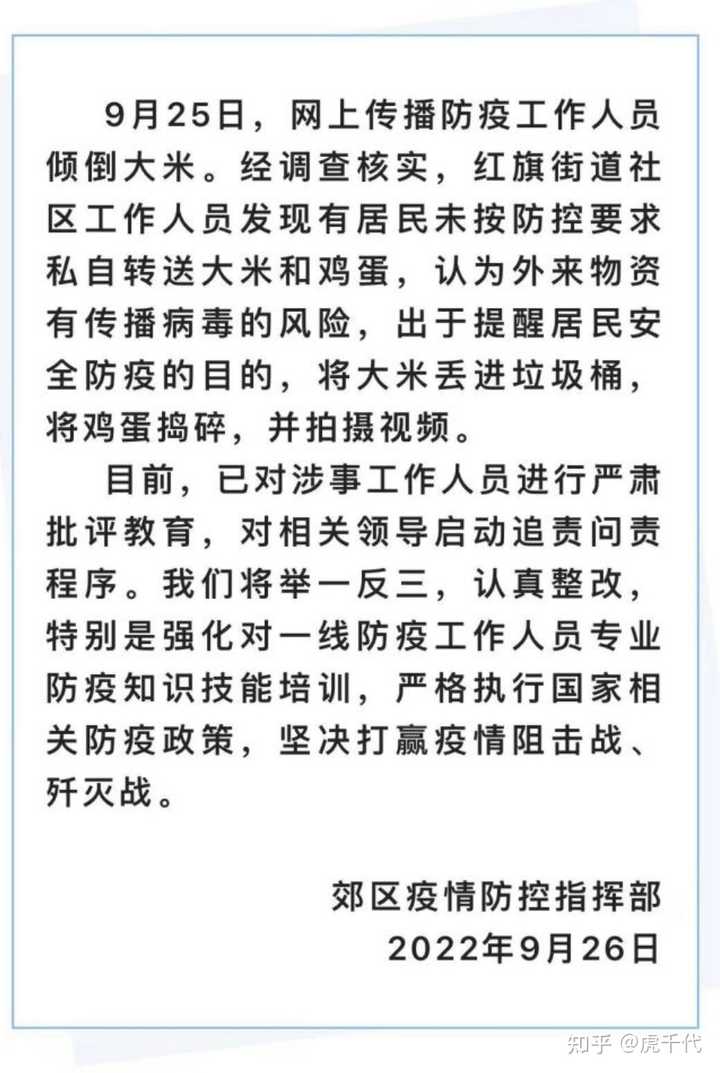

当年中学教科书中描写的万恶的资本主义时,为什么资本家宁愿将牛奶倒进河里也不免费分给穷人? |

|

斗鱼有个主播叫胡凯利,以前开外设店倒闭了就把外设都抽奖送了 后来胡凯利每次开店,评论都是“别买,倒闭会送” |

|

你猜为啥疫情的时候新闻里好像全国的物资都来了,你就是看不见 |

|

回旋镖 飞回来打脸上,人刚把创可贴贴上你非得给揭下来吗? |

|

|

|

|

为什么那么多烂尾楼宁可炸了,也不给没房子的年轻人住? |

|

几年前,有个新闻说某山区鸡蛋厂鸡蛋滞销,工人们不得不把成筐的鸡蛋扔山沟里,然后就有好事者问为什么宁愿扔了也不免费送人。答:你自己来拿。 |

|

你以为的是: 是马路边上穷人来到牛奶摊前,低声下气的说到:“行行好吧,给我一点牛奶吧!” “不给!”然后直接倒了 实际上: 牛奶厂距离城市老远,你要花钱把牛奶运到城市里,才有可能分给穷人!这运费你愿意出吗 |

|

你就算批判上天了 资本家倒牛奶,倒的也是自己生产的牛奶 人家也没把捐过来的牛奶倒垃圾桶然后硬说是捐牛奶的人捐的坏牛奶 |

|

我就遇到过一次处理滞销西瓜的瓜农,人家让我随便吃,说反正不要了。可那是好几千斤的西瓜,我一个人能吃几斤?绝大多数农场是远离闹市区,人都没几个的,想送都找不到人来拿。多数情况下,把滞销的农产品直接倒掉比运输,贮存的成本要低 |

|

资本家只会倒自己的牛奶 资本家不会逼着你把你的奶到了 |

|

|

|

|

我小时候吧,经常会冒出来一些不切实际的想法,比如全世界所有人都给我一块钱多好。 后来一寻思,不对啊 这全世界70亿人哪怕排着队给钱,算他1秒过两个人,也得35亿秒才能把钱给完。 长大了看书说万恶的资本把牛奶倒了,也不给穷人喝,我也寻思这是一回事啊 要怎么给穷人呢? 总不能穷人排着队在奶农门口张着嘴等奶吧。 那如果送上门要怎么操作呢? 小孩嘛,不懂什么物流、冷链、经济的 当时想的是挨家挨户的问谁要牛奶? 然后我又转念一想,不对啊 我家要有陌生人敲门,说免费送我牛奶,我能信啊? 他敢送,我敢喝吗? 那他就得给我解释为啥送牛奶,搞不好还得报警看看有什么阴谋 想到这,我当时就觉得如果是我,我也倒了。 我不收钱给人送奶上门,还得哄着别人收下 多贱啊我 |

|

因为你学的历史不是历史本身,那叫政治宣传册: 大萧条时期实际情况,由于奶商的极限压低收购价,奶农们为了不因为各自恶性降价出售导致奶价崩盘就会组成了一个最低价格联盟,低于此价格就谁都不许向奶商供奶,但联盟之下总有偷偷向奶商低价供奶的叛徒。 奶农们就去把这些叛徒的奶销毁。 |

|

因为你们学到的是秽史啊,真实的历史是大萧条时,奶厂压低牛奶收购价格,奶农便拒绝为奶厂供奶,但是还是有部分奶农会向奶厂偷偷供奶,于是其他奶农拦住这些奶农的供奶车,并把他们的奶给倒了,大部分的倒奶都属于这种 |

|

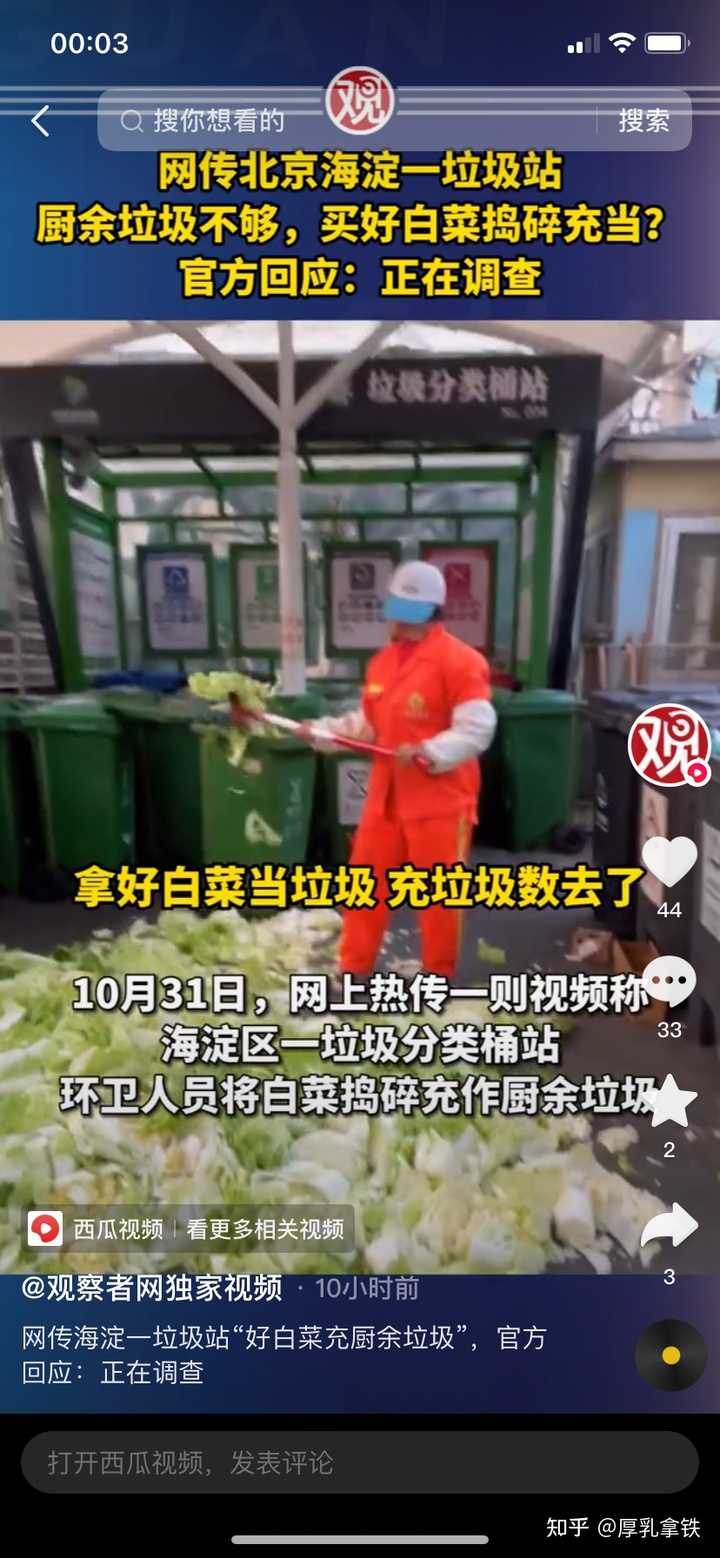

这事儿,都成回旋镖了。。 就这某些人还嘴硬,“社会主义的事儿,能叫倒吗?” |

|

因为倒牛奶时,市场上已经是供大于求。牛奶出售后的收益,连运输、分装、销售的成本都不如。这时候倒牛奶的往往根本就不是啥资本家,而是从事养殖奶牛的奶农。 如果按那些人扯的白送给穷人喝,只要这种白送给人喝的美事传到市场上,你猜会咋样?会进一步让奶业崩盘,会进一步没人买奶喝,都等着喝白送的奶了。结果就是奶业彻底玩完,运输、分装、销售人员失业,奶农彻底破产。 这就叫只管穷人喝奶,不管奶工失业,更不管奶农死活。 道德,实际该是一种自我约束,而不是慷他人之慨的道德绑架。你同情穷人就自己买奶送给穷人喝,别慷着奶工的饭碗和奶农的死活,来彰显自己的道德。这种不由自己付出,而是由别人付出代价的道德,实际是伪道德,这种所谓的善良,实际也就是伪善。 经济有经济的规律,你必须尊重经济规律,才能让经济顺利发展。部分牛奶倒掉了,供需恢复一定的平衡。而市场也知道人家宁可倒掉,也不会有白送你喝的美事,于是有需要的才会掏钱买奶。奶业职工才保得住饭碗,奶农们才不会破产。 而社会也有着社会的规律,老大爷摔倒了没钱治病,你有车有钱又扶了,于是就该当冤大头再给大爷赔上几万。简单的以道德绑架去解决问题,结果就是出更大的社会问题。倒了的老人,没人敢扶,也没人会扶。 无论经济还是社会,这种看似道德的无脑简单解决办法,往往导致更大的问题。用虚伪的善,行真实的恶。 |

|

资本家的牛奶,也是自己养殖场里的奶牛产的,你在看这个…..有一点可以肯定,这白菜肯定不是它们自己种的 |

|

|

|

|

万恶的资本主义大概也想不到会有房地产商宁可自己破产也不降价出售房产 |

|

美国的资本家万恶呗,中国的资本家就比较有良心,加点三聚氰胺就分给买不起贵奶粉的穷人了 |

|

因为奶农以卖奶维生,如果把奶分给穷人,那就一分钱都卖不出去。奶农就真饿死了。 这个故事最阴险的地方,就是把底层奶农描写为资本家。把奶农的求生行为描写为自私自利。但奶农事实上并不比一般人富裕,甚至在奶业萧条下还要更加穷困,即使他们在左左眼里掌握了不知所谓的“生产资料”。 由此可见,“资本家”是一个筐,什么都可以往里装。不由让人想起改革开放前,养多几只鸡鸭,也是搞资本主义复辟了。我劝左左粉红们还是悠着点儿,因为你们做梦都想要长江黄河倒着流。按照倒流的标准,你们也可以是资本家。你们今日把资本家的罪定的越重,来日你们的麻烦也可能越大。 |

|

|

|

|

|

这些年新闻里多的是地理得菜滞销,菜农直接毁掉得事情,这和什么资本家无关,现实里很多人东西自己不能用了,也会扔掉而不是选择给需要的人。 因为倒掉最省事,分给穷人既不省事,还可能惹事,也节省不了什么什么成本。 你让一个工人倒掉一桶牛奶,很快,花不了多少时间,但是你要把这一桶牛奶免费给穷人。 哪怕穷人自己来拿,你也要等,如果穷人不来拿你还得分发宣传 何况你还得承担穷人拿你牛奶虽然免费,但是出了问题你不能免责得风险。 现在很多连锁快餐店规定过期实际还能吃得东西,一般是销毁而不是直接丢弃,就是类似原因。 如果你是资本家,你为什么要免费分给穷人呢? 你为什么不赶紧处理掉牛奶,继续接下来该做得事情呢? 更直接牛奶都滞销没什么人买了,你还把牛奶免费给穷人,这下子彻底没人买了 所有人都来等你的过期牛奶了。 你干脆做慈善家去了。 |

|

你家种的果子没渠道卖,为什么宁愿烂地里也不送给穷人。 很傻的一个教材,什么叫“分给”。又不是喊一声,多的牛奶马上就消失到穷人肚子里。 谁去通知穷人,通知几天,哪个片区,怎么通知?牛奶要不要进生产线消毒,如果穷人提个桶来领,怎么领,直接在池子里舀还是去奶牛身上挤,还需要安排人维持秩序,还得确保过程中没有污染…… 资本家已经赔钱了还得操心这些。 |

|

在中国税法里有个概念叫视同销售,也就是说,赠送的产品送给别人,需要按照销售的价格交增值税,需要视同这些产品已销售,按照销售收入累计所得税。 而过期商品报废,可以成为企业运行成本,抵扣所得税,如果是中间商,还可以进行增值税抵扣。里外里商家的成本差异是很大的。 因此可以理解为,在目前国内立法精神方面,也是不鼓励企业将卖不出去的商品送给穷人。 |

|

不说资本家了,就说说以前有些面包店晚上卖不完的蛋糕会免费送,以显示他们家的蛋糕都是新鲜的,然后接二连三的出现,老人吃了他们家送的面包生病要告他们要赔偿,现在的蛋糕店宁愿卖不掉也不送了。 |

|

中国有六亿栋房,为什么即使炸了也不分给穷人? |

|

中国不教逻辑学,其中批判资本家拿倒牛奶这个例子,不揭示逻辑,等少年人知道社会主义国家宁愿修那么多的房子空着烂尾,也不愿发给穷人的时候,回旋镖飞回来,你拿什么解释,是国情所在?还是中国特色? |

|

以下摘自澎湃新闻 最近,各地奶农、奶企在倒牛奶,这事让人关注,一是有违中国人勤俭节约的传统美德,一是教科书上说,万恶的资本家宁愿把牛奶倒在密西西比河也不给穷人,反映了资本家的贪婪腐朽,是经济大萧条的标志。 那么问题来了,在我们有制度优越性的社会主义国家,倒牛奶事件也是经济大萧条的标志吗? 产生这样疑问的同学,显然是功课没有学好。2006年考研政治题:自2002年以来,南京、成都、石家庄等地相继发生奶农把鲜奶倒入下水道的事件。1、历史上资本主义国家经济危机时农场主把牛奶倒入大海的现象,与材料中的“倒奶事件”有何本质区别:2、为避免发生类似的?倒奶事件”,你认为地方政府应如何作为? 参考答案:1、从表象看,两者都是牛奶供给过剩。但是,前者反映的是生产社会化与生产资料资本主义私有制之间的矛盾,是资本主义生产关系与生产力矛盾的体现;后者主要是市场体系不够完善,鲜奶销售渠道不畅导致的结果,不是经济危机的征兆。 2、由于奶农和企业往往缺乏充分的信息和对市场风险足够的认识,因此,地方政府有必要予以引导和服务。如着力帮助奶农和企业进行市场预测和分析,开展事前的供需调研;制定科学、合理的产业规划,形成较为完善的农业产业化链条;采取优惠措施,帮助企业和奶农开拓乳品市场,尤其是农村市场,扩大内需;监督奶农和企业严格执行产品质量标准,促使其改进生产技术。 对于第一个答案,澎澎表示不服不行。掌握了辩证法,天黑都不怕! 而对第二个答案,澎澎需要补充。从2002年开始就有倒奶事件,十几年过去仍然存在,这反映出地方政府工作不到位,相关部门必须高度重视,主要领导亲自抓、分管领导具体抓、专职人员专门抓,千方百计保障奶农的利益。 最重要的还是理论创新。比如,从倒牛奶事件的不同处置看社会主义制度的优越性,等等。 不过这样的事,需要牙口好的人来做,澎澎做不来,不服不行。 其实上世纪30年代初的美国,倒牛奶的主力并不是资本家,而是要求政府立法实施价格管制的奶农,为此他们发起罢工,他们倒的也不是自己的牛奶,而是别的奶农的牛奶,这样做是为了防止别的奶农以低价销售牛奶。 倒别人的牛奶,让资本家去背黑锅。美国奶农使出的李代桃僵这一计,严重欺骗了广大中国人民的感情! 美国奶农倒牛奶体现资本主义腐朽没落,中国奶农倒牛奶提现社会主义市场经济优越性。 美国奶农嫁祸资本家,败坏中国人民感情! 你,学会了吗? |

|

《愤怒的葡萄》描绘了1930年代美国社会的图景,这是鲜活的资本主义教科书,美国农民的血泪史,更是无产阶级的成长史。 本次节选的是本书的第六章: ……为了这块地,爷爷消灭了印第安人,爸爸消灭了蛇。我们也许可以消灭银行——银行比印第安人和蛇都更可恶呢。我们为了保全我们的地,也许非起来斗争不可,像爸爸和爷爷那样干。…… |

|

|

田地的业主们有时到田地上来,业主的代理人来的次数更多。他们坐着门窗紧闭的小汽车来,用手指头摸摸干燥的土地,有时还用钻探机钻进地里去验验土质。那些门窗紧闭的小汽车顺着田野开来的时候,佃户们从他们那些被太阳晒得干巴巴的门前院子里不自在地望着。最后,业主方面的人把车子开进院子来,坐在车上,从摇下的车窗里跟人谈话。佃户方面的人在汽车旁边站了一会儿,随即蹲在地上,找些枝条来在尘土里写下些什么。 妇女们站在敞开的门里向外看,孩子们站在她们背后——一些脑袋尖瘦的孩子,眼睛睁得大大的,一只光脚叠在另一只光脚上,脚趾扭动着。妇女们和孩子们望着家里的男人们和业主方面的人谈话。他们默不作声。 业主方面的人有的很和气,因为他们憎恶自己所不得不做的事情;有的很生气,因为他们并不愿意残忍;有的很冷酷,因为他们早就体会到人要是不冷酷,就不能做业主。他们全都被一种大于他们自己的东西控制住了。对于那些驱策他们的数学,他们有人憎恶,有人害怕,也有人崇拜,因为那些数学可以使他们回避思想和感情。如果土地归什么银行或是什么公司所有,业主方面的人就说,银行——或是公司——必须怎样——要想怎样——坚持要怎样——非怎样不可——仿佛银行或公司是一个具有思想情感的怪物,已经把他们钳制住了似的。这些受钳制的人是不替银行或是公司负任何责任的,因为他们是人,是奴隶,而银行既是机器,同时又是主人。业主方面有一些人做了这种冷酷的、强有力的主人的奴隶,还觉得很得意。业主方面的人坐在汽车里解释着。你们知道这土地不出庄稼。你们在这里苦干了很久了,天知道。 蹲在地上的佃户方面的人点点头,感到惶惑,在尘沙里写出一些数字。是呀,他们知道,天也知道。只要不起风沙就好了。只要这尘沙在土地上待住,也许就不至于这么糟糕。 业主方面的人继续往下说,把话头渐渐转到本题:你们也知道这土地越来越糟了。你们知道棉花对土地起了什么作用;它把土地弄坏了,吸干了地里的血。 蹲着的人点点头——他们知道,天也知道。如果他们可以轮种各样的庄稼,那也许可以给土地输回血液吧。 噢,现在来不及了。于是业主方面的人把那比他们自己更强有力的怪物的行动和见解解释一番。一个人只要能吃饱,缴得出捐税,他就能保住土地;这是办得到的。 是的,在得不到收成、不得不向银行借钱那一天以前,一个人是可以这么维持下去的。 但是——你要知道,一个银行或是一个公司却不能这么办,因为它们是既不呼吸空气,也不吃肋条肉的。它们所呼吸的是利润,所吃的是资本的息金。如果它们得不到这个,它们就会死去,正如你呼吸不到空气,吃不到饭就会死去一样。这是可叹的事,但是事实却是如此。恰恰如此。 蹲着的男人们抬起眼睛来,想要理解这个问题。让我们凑合着对付下去不行吗?明年也许是个丰年。天知道明年棉花的收成会有多么好。况且还有打不完的仗——天知道棉花的市价会涨到多么高。人家不是用棉花做炸药、做军装吗?只要老打仗,棉花的价钱就会涨上天。明年也许会这样吧。他们以探询的眼色抬头望着。 我们是不能指望这一点的。银行这怪物非经常有盈利不可。它不能等待,它会死的。要知道租税老在不断地增加。如果这怪物停止发展,它就死了。它是不能停顿在一个限度之内的。 柔软的手指头开始轻敲着车窗的框子,粗硬的指头却紧捏着枝条,不自在地乱画。在佃户人家被太阳晒得干巴巴的门口,妇女们叹叹气,把两只脚调换了一下,将原来在下面的一只放在另一只上面,脚趾仍旧在扭动着。一群狗走近业主的汽车去嗅一嗅,在四只轮胎上撒了尿。鸡在阳光照射的尘沙里躺着,抖一抖身上的羽毛,要把尘沙抖到皮肤上去,起沙浴的作用。小猪圈里的猪吃着肮脏的残剩的饲料,以怀疑的神情哼叫着。 蹲着的男人们又低下头来望着地上。你们叫我们怎么办呢?收成我们不能再少分了——我们现在已经快要饿死了。孩子们老是吃不饱。我们浑身破破烂烂,穿不上衣服。如果不是左邻右舍都和我们一样,我们都不好意思去做礼拜了。 最后,业主方面的人终于讲到了本题。租佃制度再也行不通了。一个人开一台拖拉机能代替十二三户人家。只要付给他一些工资,就可以得到全部收成。我们只得这么办了。我们并不喜欢这么办,但是那怪物病了。那怪物出了毛病,不这么办就不行。 但是你们老种棉花,会把土地毁掉的。 我们也知道。我们要趁这地还没有完蛋之前,赶快种出棉花来。然后我们就把地卖掉。东部有好多人家想要买些地呢。 佃户方面的人惊恐地抬头望着。可是我们怎么办呢?我们靠什么吃饭呢? 你们非离开这地方不可。拖拉机要开进这院子里来了。 现在,蹲着的男人们愤怒地站了起来。从前爷爷为了占领这块地,得把印第安人打死,把他们赶跑。爸爸出生在这里,他清除了野草,消灭了蛇。后来遇到荒年,他只得借些钱。接着我们又在这里出世了。在这道门里——我们的孩子就是在这里出世的。于是爸又只得去借点钱。结果土地归了银行,可是我们还留在这里,我们还可以分得一点自己种出的东西。 这一切我们都知道。这并不是我们的事,而是银行的事。银行和人不一样。或者也可以说,有五万英亩地的业主,他也跟人不一样。这就是那个怪物了。 话倒是对的——佃户方面的人大声说——可这究竟是我们的地呀。地是我们量出来的,也是我们开垦出来的。我们在这地上出世,在这地上卖命,在这地上死去。即使地不济事,究竟还是我们的。在这里生,在这里死,在这里干活儿——所以这块地应该算是我们的。所有权应该以这些为凭,不应该凭着一张写着数字的文契。 对不起。这不怨我们。只怨那怪物。银行跟人是不一样的。 对,但是银行毕竟也是人开的呀。 不,那你就弄错了——大错特错了。银行是跟人完全不同的一种东西。银行所做的事情,往往是银行里的人个个都讨厌的,而银行偏要这么做。银行这种东西是在人之上的。我告诉你吧,它是个怪物。人造出了银行,却又控制不住它。 佃户们叫喊道,为了这块地,爷爷消灭了印第安人,爸爸消灭了蛇。我们也许可以消灭银行——银行比印第安人和蛇都更可恶呢。我们为了保全我们的地,也许非起来斗争不可,像爸爸和爷爷那样干。 于是业主方面的人动气了。你们非走不可。 不过这是我们的地呀——佃户方面的人叫喊道——我们…… 不,这地是归银行这怪物管理的。你们非走不可。 我们要像爷爷当初在印第安人来了的时候那样,拿起枪来。看你们怎么办! 哼——首先有警察,其次是军队。如果你们赖在这里,你们就是犯了盗窃罪,如果你们杀了人赖在这里,你们就成了凶手。那怪物并不是人,可是它却能叫人做它所要做的事情。 可是如果我们走开,我们到什么地方去呢?我们怎么去呢?我们没有钱呀。 对不起——业主方面的人说道——这银行,这五万英亩地的业主是不会负责的。你们所种的地并不是你们自己的。你们搬出了地界,也许可以在秋天摘摘棉花。你们也许可以领些救济金来过活儿。你们为什么不往西部去,到加利福尼亚去呢?那边有工作,天气也不冷。嗐,你们无论走到什么地方,一伸手就可以摘到橙子,经常会有庄稼活儿给你们做。你们为什么不上那儿去呢?说完,业主方面的人就开动汽车,一溜烟跑掉了。 佃户方面的人又蹲在地上,用枝条拨弄着尘沙,想着心事。他们晒黑了的脸是阴沉的,太阳熬炼过的眼睛是发亮的。妇女们从门口小心翼翼地移步到自己的男人身边,孩子们跟在妇女们后面,小心翼翼地悄悄走着,打算跑开。年纪大些的男孩子蹲在他们的父亲身边,因为这么一来,他们就显得像大人了。过了一会儿,妇女们问道,他们要怎么样? 男人们抬起头来望了一会儿,他们的眼光显出一股沉痛的神情。我们要滚蛋了。他们要派一台拖拉机和一个管理员来。像工厂一样。 我们上哪儿去呢?妇女们问道。 我们不知道。我们不知道。 于是妇女们一声不响地赶快回到屋里去,还撵着孩子们在她们前面走。她们知道那么忧伤和烦恼的男人即使对自己心爱的人也是会发脾气的。所以她们便撇下了男人,让他们蹲在尘沙上盘算,想着心事。 过了一会儿,那些佃农朝四周张望了一下——看看十年前装置的那个抽水机,那上面有一个鹅颈形的把手,喷水管的嘴上有一些铁花;看一看那块杀过上千只鸡的砧板;看一看放在棚舍里的手犁和挂在棚舍梁上的那只别致的摇篮。 屋子里,孩子们聚集在女人身边。我们怎么办,妈?我们上哪儿去? 妇女们说,我们还不知道。出去玩玩吧,但是不要走近爸爸身边。如果你们到他身边去,他也许要打你们。妇女们又继续工作了,可是她们却一直望着蹲在尘沙里想着心事、大伤脑筋的男人们。 几辆拖拉机从大路上开过来,开进了田野,它们是些像虫子一般爬行的巨物,有那么大的了不起的气力。它们在地面上爬行着,把履带滚下来,在地面上滚过,又把它卷上去。拖拉机停歇的时候,那上面的柴油机啪嗒啪嗒地响着;一开动,便轰隆轰隆地响起来,渐渐变成单调的吼声了。这些狮子鼻的怪物扬起尘沙,向尘沙里钻进去。它们一直越过原野,越过篱笆,越过家家户户门前的院子,沿着一条条的直线来回地闯过许多水沟。它们并不是在地面上跑,而是在自己的路基上跑。它们完全不把高冈、低谷、水道、篱笆和房屋等东西放在眼里。 坐在铁座上的那个人,看上去并不像一个人;他戴着手套和风镜,鼻子和嘴上套着橡皮质的防沙面具,他是那怪物的一部分,是个坐着的机器人。汽缸的雷鸣声响彻了原野,与空气和大地合为一体,大地和空气都跟着颤动起来,发出低沉的声响。驾驶员控制不住它——它一直越过原野,划破十多个农庄,又一直转回来。只要拨动一下操纵杆,就可以改变拖拉机的方向,但是驾驶员的两只手却不能随意拨动,因为造出拖拉机和派出拖拉机来的那个怪物仿佛控制了驾驶员的一双手,控制了他的脑子和筋肉,给他戴上了眼罩,套上了口罩——蒙住了他的心灵,堵住了他的嘴,掩盖了他的理智,制止了他的抗议。他看不见土地的真面目,嗅不出土地的真气息;他的两脚踏不到泥土,感觉不到大地的温暖和力量。他坐在铁座上,踏着铁踏板。他对自己的力量的扩张既不会欢呼,也不会遏制;既不会诅咒,也不会鼓励。因此他对自己也就不能鼓舞、鞭策、诅咒或是激动了。他对土地既不熟悉,也没有所有权;既不信赖,也无所求。如果撒下的种子没有发芽,那也不相干。如果长出来的幼芽在大旱天枯萎了,或是在大雨里淹死了,那也与驾驶员不相干,正如不关拖拉机的事一样。 驾驶员并不比银行更爱土地。他尽可以夸赞拖拉机——赞美它那机器制成的表面,它那雄伟的力量,它那些汽缸震耳的吼声,但是这毕竟不是他的拖拉机。拖拉机后边滚着亮晃晃的圆盘耙,用锋刃划开土地——这不像耕作,倒像施外科手术。一排圆盘耙把土划开,掀到右边,另一排圆盘耙又把它划开,掀到左边;圆盘耙的锋刃都被掀开的泥土擦得亮亮的。圆盘耙后面拖着的铁齿耙又把小小的泥块划开,把土均匀地铺平。耙后是长形的播种机——在翻砂厂里装置的十二根弯曲的铁管,由齿轮推动着,按部就班地在土里插进抽出。驾驶员坐在铁座上,看着自己无意划出的那些直线,感到得意;看着并非自己所有和他所不爱的拖拉机,也感到得意;看着自己所不能控制的那股力量,也感到得意。庄稼生长起来和收割的时候,没有人用手指头捏碎过一撮泥土,让土屑从他的指尖当中漏下去。没有人接触过种子,或是渴望它成长起来。人们吃着并非他们所种植的东西,大家跟面包都没什么关系了。土地在铁的机器底下受苦受难,在机器底下渐渐死去。因为既没有人爱它,也没有人恨它;既没有谁为它祈祷,也没有谁诅咒它。 中午,拖拉机驾驶员往往在一家佃户人家的近旁停下来,打开他的一包午餐:蜡纸包着的三明治、白面包、泡菜和乳酪,还有一块名叫“斯帕姆”的、有机器零件图案商标的馅饼。他毫无滋味地吃着。还没有搬走的佃户们出来看他,他摘下护目镜和橡皮质的防沙面具,眼睛周围留着一道白圈儿,鼻子和嘴的周围也留着一个大白圈儿,人家就趁这时候以好奇的神情望着他。拖拉机的排气管啪嗒啪嗒地继续响着,因为燃料十分低廉,与其重新烘热柴油机的管口,使它开动,不如让它转个不停。好奇的孩子们紧紧地聚拢来,这些衣衫褴褛的小孩一面望着,一面吃着煎过的面包。他们很馋地看着三明治被揭开了包装纸,他们那因嘴馋而变得特别灵敏的鼻子嗅到了泡菜、乳酪和“斯帕姆”的气味。他们没有对驾驶员讲话,只望着他的手把食物送到嘴里去。他们没有看他咀嚼,他们的眼睛紧盯着那只拿三明治的手。过了一会儿,那不能离开这地方的佃户走出来,蹲在拖拉机旁边的阴影里。 “嘿,原来你是乔·戴维斯的儿子呀!” “不错。”驾驶员说。 “那么你为什么干这种活计来跟自己人作对呢?” “三块钱一天。我东奔西跑地找饭吃——总是找不到,实在找烦了。我有老婆孩子。我们非吃饭不可。三块钱一天,每天都能拿到手。” “这倒是对的,”佃户说,“可是为了你一天拿三块钱,就有一二十户人家什么也吃不到了。为了你一天拿三块钱,差不多就有一百人只得出去流落在路上。是不是这么回事?” 驾驶员说道:“不能往这上面想。我得顾自己的孩子,三块钱一天,每天都能拿到手。时代变了,先生,你还不知道吗?你要是没有两千、五千、一万英亩地和一台拖拉机,就不能靠种地过活。种庄稼的地再也不会给我们这样的人受用了。你不能造汽车,不是电话公司,光只乱嚷一阵是不行的。哎,现在种庄稼也是这样。你简直无可奈何。你干脆想办法到什么地方去一天赚三块钱吧。这是唯一的办法了。” 佃户思量着。“这事情想起来也真是奇怪。一个人如果有了一份小产业,这份产业就跟他分不开,就和他融为一体。如果他有了田产,能在田地上走,能给田地做些安排,收成不好的时候他发愁,雨下到地上的时候他就快活,那么这块田地就和他分不开,他就会因为有了这份产业,多少神气一些。即使他并不顺当,他有了一份田产,也总是很神气的。这是实话。” 那佃户又思量着。“可是如果让一个人得了一份田产,他自己看不见,又没时间去亲自照料,也不能在上面走走,那么,产业就是人的主宰了。他不能照他的心意行事,也不能随意转念头。产业成了人的主宰,而且比他更强大。他自己却很渺小,并不神气。只有他的产业才算神气——他成了他的产业的仆人了。这也是实话。” 驾驶员使劲嚼着那块有商标的馅饼,把硬皮抛掉。“时代变了,你还不知道吗?你转那种念头是养不活儿女的。快去一天挣三块钱,养活儿女吧。你别管旁人的儿女,只顾自己的儿女就是了。你讲那一套道理,就算出了名,一天也挣不到三块钱。如果你除了一天挣三块钱外,还转着别的念头,大老板们就不会一天给你三块钱。” “为了你那三块钱,差不多有一百人要流落在路上。我们有什么地方好去呢?” “这倒提醒我了,”驾驶员说,“你最好是马上搬出去。我吃完了饭,就要穿过你门前的院子了。” “早上你把水井填掉了。” “我知道。我得照直线开才行。我吃完了饭,就得穿过你门前的院子。得照直线开。噢,你认得我老爹乔·戴维斯,所以我才对你老实说。我接到了命令,每到有人家不肯搬出的地方——如果我闯了祸,你知道吧,就是开得太近了,把屋子撞塌一点——那我还可以多得两块钱奖赏。要知道,我最小的孩子还没穿过鞋呢。” “这屋子是我亲手盖成的。敲直了许多旧钉子,才盖了屋顶。椽子是用铁丝扎在长桁条上的。这是我的屋子。我亲手盖的。你要撞倒它,我就在窗口里拿枪对付你。只等你开得够近了,我就像打兔子似的,一枪把你干掉。” “这不是我的事。我也没法。如果我不那么办,我就要失业。你想——你打死了我又会怎样呢?人家只会把你绞死罢了,可是你还没上绞架,就会有另外一个开拖拉机的家伙把这屋子撞倒。你并没把该死的人打死。” “这话有理,”佃户说,“是谁给你下的命令?我要把他找到。应该杀了他才对。” “你错了。他是奉银行的命令的。银行告诉他,‘把那些人通通撵走,否则唯你是问’。” “那么,银行有行长,有董事会。我要把来复枪装好了弹药,闯进银行去。” 驾驶员说道:“有人告诉我,银行也是奉了东部发来的命令。那命令上说:‘赶紧叫这块地赚钱,否则我们就要叫你关门。’” “这么说还有个完吗?我们到底可以把什么人一枪打死?不先把那个叫我饿死的人杀掉,我是决不甘心饿死的。” “我不知道。也许你开枪打死谁都不行。也许问题根本就不在人。也许正像你所说的,是产业本身在作怪。不管怎样,反正我已经把我收到的命令告诉你了。” “我得想一想,”佃户说,“我们都得盘算盘算才行。要阻止这件事是有办法的。这不像打雷或是地震。这是人为的祸患,靠老天爷保佑,我们是可以改变过来的。”佃户坐在他的门口,驾驶员把机器弄得轰隆轰隆响了一阵,便开动了。拖拉机上的履带一起一落,一弯一曲,铁耙梳理着土壤,播种机的铁杆插进地里。拖拉机划过门前的院子,于是原先给脚踩得硬实的地面变成撒过种子的田地,拖拉机又从这里划过;不曾划过的空地只有十英尺宽了。于是他又开回来。钢铁的护板撞着了屋角,把墙撞倒,使小屋兜底一动,便向一边坍塌下去,像一只甲虫似的被粉碎了。驾驶员戴着护目镜,鼻子和嘴上蒙着橡皮面具。拖拉机继续沿着直线划过去,空气和地面便随着它的轰隆声而震荡了。那个佃户手里拿着来复枪,在它后面眼睁睁地望着。他的老婆在他身边,老老实实的孩子们站在后面。他们大家都眼睁睁地望着远去的拖拉机。 |

|

|

THE OWNERS of the land came onto the land, or more often a spokesman for the owners came. They came in closed cars, and they felt the dry earth with their fingers, and sometimes they drove big earth augers into the ground for soil tests. The tenants, from their sun-beaten dooryards, watched uneasily when the closed cars drove along the fields. And at last the owner men drove into the dooryards and sat in their cars to talk out of the windows. The tenant men stood beside the cars for a while, and then squatted on their hams and found sticks with which to mark the dust. In the open doors the women stood looking out, and behind them the children—corn-headed children, with wide eyes, one bare foot on top of the other bare foot, and the toes working. The women and the children watched their men talking to the owner men. They were silent. Some of the owner men were kind because they hated what they had to do, and some of them were angry because they hated to be cruel, and some of them were cold because they had long ago found that one could not be an owner unless one were cold. And all of them were caught in something larger than themselves. Some of them hated the mathematics that drove them, and some were afraid, and some worshiped the mathematics because it provided a refuge from thought and from feeling. If a bank or a finance company owned the land, the owner man said, The Bank—or the Company—needs—wants—insists—must have—as though the Bank or the Company were a monster, with thought and feeling, which had ensnared them. These last would take no responsibility for the banks or the companies because they were men and slaves, while the banks were machines and masters all at the same time. Some of the owner men were a little proud to be slaves to such cold and powerful masters. The owner men sat in the cars and explained. You know the land is poor. You’ve scrabbled at it long enough, God knows. The squatting tenant men nodded and wondered and drew figures in the dust, and yes, they knew, God knows. If the dust only wouldn’t fly. If the top would only stay on the soil, it might not be so bad. The owner men went on leading to their point: You know the land’s getting poorer. You know what cotton does to the land; robs it, sucks all the blood out of it. The squatters nodded—they knew, God knew. If they could only rotate the crops they might pump blood back into the land. Well, it’s too late. And the owner men explained the workings and the thinkings of the monster that was stronger than they were. A man can hold land if he can just eat and pay taxes; he can do that. Yes, he can do that until his crops fail one day and he has to borrow money from the bank. But—you see, a bank or a company can’t do that, because those creatures don’t breathe air, don’t eat side-meat. They breathe profits; they eat the interest on money. If they don’t get it, they die the way you die without air, without side-meat. It is a sad thing, but it is so. It is just so. The squatting men raised their eyes to understand. Can’t we just hang on? Maybe the next year will be a good year. God knows how much cotton next year. And with all the wars—God knows what price cotton will bring. Don’t they make explosives out of cotton? And uniforms? Get enough wars and cotton’ll hit the ceiling. Next year, maybe. They looked up questioningly. We can’t depend on it. The bank—the monster has to have profits all the time. It can’t wait. It’ll die. No, taxes go on. When the monster stops growing, it dies. It can’t stay one size. Soft fingers began to tap the sill of the car window, and hard fingers tightened on the restless drawing sticks. In the doorways of the sun-beaten tenant houses, women sighed and then shifted feet so that the one that had been down was now on top, and the toes working. Dogs came sniffing near the owner cars and wetted on all four tires one after another. And chickens lay in the sunny dust and fluffed their feathers to get the cleansing dust down to the skin. In the little sties the pigs grunted inquiringly over the muddy remnants of the slops. The squatting men looked down again. What do you want us to do? We can’t take less share of the crop—we’re half starved now. The kids are hungry all the time. We got no clothes, torn an’ ragged. If all the neighbors weren’t the same, we’d be ashamed to go to meeting. And at last the owner men came to the point. The tenant system won’t work any more. One man on a tractor can take the place of twelve or fourteen families. Pay him a wage and take all the crop. We have to do it. We don’t like to do it. But the monster’s sick. Something’s happened to the monster. But you’ll kill the land with cotton. We know. We’ve got to take cotton quick before the land dies. Then we’ll sell the land. Lots of families in the East would like to own a piece of land. The tenant men looked up alarmed. But what’ll happen to us? How’ll we eat? You’ll have to get off the land. The plows’ll go through the dooryard. And now the squatting men stood up angrily. Grampa took up the land, and he had to kill the Indians and drive them away. And Pa was born here, and he killed weeds and snakes. Then a bad year came and he had to borrow a little money. An’ we was born here. There in the door— our children born here. And Pa had to borrow money. The bank owned the land then, but we stayed and we got a little bit of what we raised. We know that—all that. It’s not us, it’s the bank. A bank isn’t like a man. Or an owner with fifty thousand acres, he isn’t like a man either. That’s the monster. Sure, cried the tenant men, but it’s our land. We measured it and broke it up. We were born on it, and we got killed on it, died on it. Even if it’s no good, it’s still ours. That’s what makes it ours—being born on it, working it, dying on it. That makes ownership, not a paper with numbers on it. We’re sorry. It’s not us. It’s the monster. The bank isn’t like a man. Yes, but the bank is only made of men. No, you’re wrong there—quite wrong there. The bank is something else than men. It happens that every man in a bank hates what the bank does, and yet the bank does it. The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it. The tenants cried, Grampa killed Indians, Pa killed snakes for the land. Maybe we can kill banks—they’re worse than Indians and snakes. Maybe we got to fight to keep our land, like Pa and Grampa did. And now the owner men grew angry. You’ll have to go. But it’s ours, the tenant men cried. We—— No. The bank, the monster owns it. You’ll have to go. We’ll get our guns, like Grampa when the Indians came. What then? Well—first the sheriff, and then the troops. You’ll be stealing if you try to stay, you’ll be murderers if you kill to stay. The monster isn’t men, but it can make men do what it wants. But if we go, where’ll we go? How’ll we go? We got no money. We’re sorry, said the owner men. The bank, the fifty-thousand-acre owner can’t be responsible. You’re on land that isn’t yours. Once over the line maybe you can pick cotton in the fall. Maybe you can go on relief. Why don’t you go on west to California? There’s work there, and it never gets cold. Why, you can reach out anywhere and pick an orange. Why, there’s always some kind of crop to work in. Why don’t you go there? And the owner men started their cars and rolled away. The tenant men squatted down on their hams again to mark the dust with a stick, to figure, to wonder. Their sunburned faces were dark, and their sun-whipped eyes were light. The women moved cautiously out of the doorways toward their men, and the children crept behind the women, cautiously, ready to run. The bigger boys squatted beside their fathers, because that made them men. After a time the women asked, What did he want? And the men looked up for a second, and the smolder of pain was in their eyes. We got to get off. A tractor and a superintendent. Like factories. Where’ll we go? the women asked. We don’t know. We don’t know. And the women went quickly, quietly back into the houses and herded the children ahead of them. They knew that a man so hurt and so perplexed may turn in anger, even on people he loves. They left the men alone to figure and to wonder in the dust. After a time perhaps the tenant man looked about—at the pump put in ten years ago, with a goose-neck handle and iron flowers on the spout, at the chopping block where a thousand chickens had been killed, at thehand plow lying in the shed, and the patent crib hanging in the rafters over it. The children crowded about the women in the houses. What we going to do, Ma? Where we going to go? The women said, We don’t know, yet. Go out and play. But don’t go near your father. He might whale you if you go near him. And the women went on with the work, but all the time they watched the men squatting in the dust—perplexed and figuring. The tractors came over the roads and into the fields, great crawlers moving like insects, having the incredible strength of insects. They crawled over the ground, laying the track and rolling on it and picking it up. Diesel tractors, puttering while they stood idle; they thundered when they moved, and then settled down to a droning roar. Snub-nosed monsters, raising the dust and sticking their snouts into it, straight down the country, across the country, through fences, through dooryards, in and out of gullies in straight lines. They did not run on the ground, but on their own roadbeds. They ignored hills and gulches, water courses, fences, houses. The man sitting in the iron seat did not look like a man; gloved, goggled, rubber dust mask over nose and mouth, he was a part of the monster, a robot in the seat. The thunder of the cylinders sounded through the country, became one with the air and the earth, so that earth and air muttered in sympathetic vibration. The driver could not control it— straight across country it went, cutting through a dozen farms and straight back. A twitch at the controls could swerve the cat’, but the driver’s hands could not twitch because the monster that built the tractor, the monster that sent the tractor out, had somehow got into the driver’s hands, into his brain and muscle, had goggled him and muzzled him— goggled his mind, muzzled his speech, goggled his perception, muzzled his protest. He could not see the land as it was, he could not smell the land as it smelled; his feet did not stamp the clods or feel the warmth and power of the earth. He sat in an iron seat and stepped on iron pedals. He could not cheer or beat or curse or encourage the extension of his power, and because of this he could not cheer or whip or curse or encourage himself. He did not know or own or trust or beseech the land. If a seed dropped did not germinate, it was nothing. If the young thrusting plant withered in drought or drowned in a flood of rain, it was no more to the driver than to the tractor. He loved the land no more than the bank loved the land. He could admire the tractor—its machined surfaces, its surge of power, the roar of its detonating cylinders; but it was not his tractor. Behind the tractor rolled the shining disks, cutting the earth with blades—not plowing but surgery, pushing the cut earth to the right where the second row of disks cut it and pushed it to the left; slicing blades shining, polished by the cut earth. And pulled behind the disks, the harrows combing with iron teeth so that the little clods broke up and the earth lay smooth. Behind the harrows, the long seeders—twelve curved iron penes erected in the foundry, orgasms set by gears, raping methodically, raping without passion. The driver sat in his iron seat and he was proud of the straight lines he did not will, proud of the tractor he did not own or love, proud of the power he could not control. And when that crop grew, and was harvested, no man had crumbled a hot clod in his fingers and let the earth sift past his fingertips. No man had touched the seed, or lusted for the growth. Men ate what they had not raised, had no connection with the bread. The land bore under iron, and under iron gradually died; for it was not loved or hated, it had no prayers or curses. At noon the tractor driver stopped sometimes near a tenant house and opened his lunch: sandwiches wrapped in waxed paper, white bread, pickle, cheese, Spam,1 a piece of pie branded like an engine part. He ate without relish. And tenants not yet moved away came out to see him, looked curiously while the goggles were taken off, and the rubber dust mask, leaving white circles around the eyes and a large white circle around nose and mouth. The exhaust of the tractor puttered on, for fuel is so cheap it is more efficient to leave the engine running than to heat the Diesel nose for a new start. Curious children crowded close, ragged children who ate their fried dough as they watched. They watched hungrily the unwrapping of the sandwiches, and their hunger-sharpened noses smelled the pickle, cheese, and Spam. They didn’t speak to the driver. They watched his hand as it carried food to his mouth. They did not watch him chewing; their eyes followed the hand that held the sandwich. After a while the tenant who could not leave the place came out and squatted in the shade beside the tractor. “Why, you’re Joe Davis’s boy!’’ “Sure,“the driver said. “Well, what you doing this kind of work for—against your own people?“ “Three dollars a day. I got damn sick of creeping for my dinner—and not getting it. I got a wife and kids. We got to eat. Three dollars a day, and it comes every day.“ “That’s right,“ the tenant said. “But for your three dollars a day fifteen or twenty families can’t eat at all. Nearly a hundred people have to go out and wander on the roads for your three dollars a day. Is that right?“ And the driver said, “Can’t think of that. Got to think of my own kids. Three dollars a day, and it comes every day. Times are changing, mister, don’t you know? Can’t make a living on the land unless you’ve got two, five, ten thousand acres and a tractor. Crop land isn’t for little guys like us any more. You don’t kick up a howl because you can’t make Fords, or because you’re not the telephone company. Well, crops are like that now. Nothing to do about it. You try to get three dollars a day someplace. That’s the only way.“ The tenant pondered. “Funny thing how it is. If a man owns a little property, that property is him, it’s part of him, and it’s like him. If he owns property only so he can walk on it and handle it and be sad when it isn’t doing well, and feel fine when the rain falls on it, that property is him, and some way he’s bigger because he owns it. Even if he isn’t successful he’s big with his property. That is so.“ And the tenant pondered more. “But let a man get property he doesn’t see, or can’t take time to get his fingers in, or can’t be there to walk on it—why, then the property is the man. He can’t do what he wants, he can’t think what he wants. The property is the man, stronger than he is. And he is small, not big. Only his possessions are big—and he’s the servant of his property. That is so, too.“ The driver munched the branded pie and threw the crust away. “Times are changed, don’t you know? Thinking about stuff like that don’t feed the kids. Get your three dollars a day, feed your kids. You got no call to worry about anybody’s kids but your own. You get a reputation for talking like that, and you’ll never get three dollars a day. Big shots won’t give you three dollars a day if you worry about anything but your three dollars a day.“ “Nearly a hundred people on the road for your three dollars. Where will we go?“ “And that reminds me,“ the driver said, “you better get out soon. I'm going through the dooryard after dinner.“ “You filled in the well this morning.“ “I know. Had to keep the line straight. But I'm going through the dooryard after dinner. Got to keep the lines straight. And—well, you know Joe Davis, my old man, so I’ll tell you this. I got orders wherever there’s a family not moved out—if I have an accident—you know, get too close and cave the house in a little—well, I might get a couple of dollars. And my youngest kid never had no shoes yet.“ “I built it with my hands. Straightened old nails to put the sheathing on. Rafters are wired to the stringers with baling wire. It’s mine. I built it. You bump it down—I'll be in the window with a rifle. You even come too close and I’ll pot you like a rabbit.“ “It’s not me. There’s nothing I can do. Ill lose my job if I dont do it. And look—suppose you kill me? They’ll just hang you, but long before you’re hung there'll be another guy on the tractor, and he’ll bump the house down. You’re not killing the right guy.“ “That’s so,“ the tenant said. “Who gave you orders? I’ll go after him. He’s the one to kill.’’ “You’re wrong. He got his orders from the bank. The bank told him, ‘Clear those people out or it’s your job.’“ “Well, there’s a president of the bank. There’s a board of directors. I’ll fill up the magazine of the rifle and go into the bank.“ The driver said, “Fellow was telling me the bank gets orders from the East. The orders were, ‘Make the land show profit or we’ll close you up.’ “ “But where does it stop? Who can we shoot? I don’t aim to starve to death before I kill the man that’s starving me.“ “I don’t know. Maybe there’s nobody to shoot. Maybe the thing isn’t men at all. Maybe, like you said, the property’s doing it. Anyway I told you my orders.“ “I got to figure,’’ the tenant said. “We all got to figure. There’s some way to stop this. It’s not like lightning or earthquakes. We’ve got a bad thing made by men, and by God that’s something we can change.’’ The tenant sat in his doorway, and the driver thundered his engine and started off, tracks falling and curving, harrows combing, and the phalli of the seeder slipping into the ground. Across the dooryard the tractor cut, and the hard, foot-beaten ground was seeded field, and the tractor cut through again; the uncut space was ten feet wide. And back he came. The iron guard bit into the house-corner, crumbled the wall, and wrenched the little house from its foundation so that it fell sideways, crushed like a bug. And the driver was goggled and a rubber mask covered his nose and mouth. The tractor cut a straight line on, and the air and the ground vibrated with its thunder. The tenant man stared after it, his rifle in his hand. His wife was beside him, and the quiet children behind. And all of them stared after the tractor. |

|

|

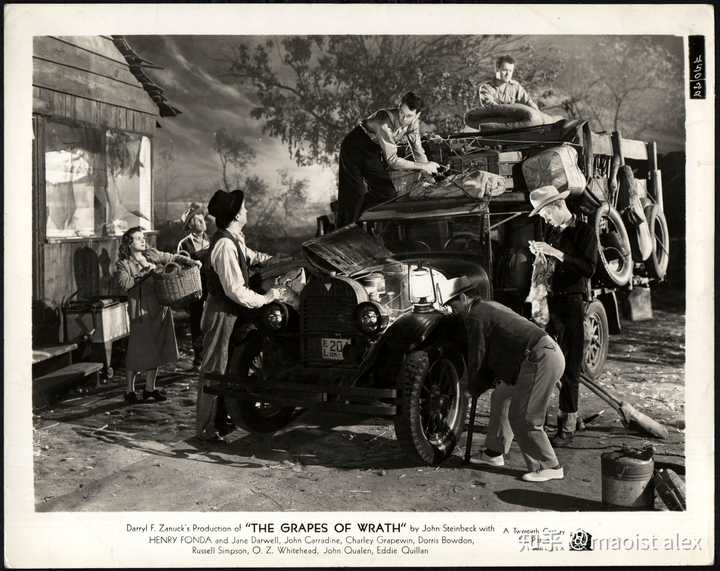

电影《愤怒的葡萄》剧照 |

|

你为什么宁愿在这里玩手机到处提问,也不愿意到街上去给老百姓进行义务劳动 |

|

其实很简单,如果分给穷人的话,那么顾客就不会买了,等着领白送的。 |

|

说回旋镖的,我寻思这个回旋镖不是改革开放的时候就已经来过一次了吗?怎么连回旋镖都要炒冷饭啊。 倒牛奶是因为资本主义市场经济生产过剩导致的。 改革开放的时候就已经正义切割过资本主义和市场经济了。 除了倒牛奶,当年的马科长“别说了”归根结底也是市场经济生产过剩的锅。 怎么到了现在还有人觉得回旋镖今天才砸中啊。 不会是上课没听讲吧。 |

|

|

| [收藏本文] 【下载本文】 |

| 上一篇文章 下一篇文章 查看所有文章 |

|

|

|

| 股票涨跌实时统计 涨停板选股 分时图选股 跌停板选股 K线图选股 成交量选股 均线选股 趋势线选股 筹码理论 波浪理论 缠论 MACD指标 KDJ指标 BOLL指标 RSI指标 炒股基础知识 炒股故事 |

| 网站联系: qq:121756557 email:121756557@qq.com 天天财汇 |